Da Bear’s Perspectives

By Ron A. Rhoades, JD, CFP®

Associate Professor of Finance,

Gordon Ford College of Business

Director, Personal Financial

Planning Program, Western Kentucky University

Financial Advisor and Content Specialist,

ARGI Investment Services, LLC

To contact Ron, please email: bear@argi.net.

Will High Rates of

Inflation Return?

As I traveled over the past two

months visiting colleagues and clients across the eastern United States, it was

indeed a pleasure to get out. And I had a greater appreciation for the small

things – the laughter of children, the smiles on the faces of often-overworked

servers, and greetings of hotel desk clerks. My biggest takeaway – it sure was

nice to get out and connect with other people again!

“Da Bear’s Perspective” is a new

publication designed to offer insights into both current topics of interest to

investors, as well as insights into obtaining the most out of life. I hope to

educate and inform through a “deeper dive” into many of the economic and

capital markets issues. And, at times, I hope to share insights that may lead

my readers to lead more fulfilling lives.

In this edition, I focus on a

question often posed as I met with colleagues and clients – fears of high

inflation.

Executive

Summary

Much of the recent rise in

prices – particularly in used cars and housing – is likely temporary in nature.

In particular, used car prices – a major contributor to the past year’s rate of

inflation – will likely fall over the next two years. Home prices will likely

not increase as much, as more inventory from builders becomes available over

the next few years. This suggests that much of the recent inflation seen – 5.7%

from June 2020 to June 2021 – is “transitory.”

However, the surge in commodity

prices (which prices can swing widely over time), and the substantial increase

in wages, suggest that the rate of inflation may continue. The large increase

in the money supply can also lead to inflation, particularly if the velocity of

money (i.e., the rate of money changing hands in the economy) picks up

if interest rates rise (and banks have more incentive to lend). A wage-price

spiral, last seen in the 1970’s and 1980’s, may serve as a trigger which leads

to higher interest rates.

In Da Bear’s view,

a 25% or greater chance of non-transitory (embedded) inflation exists.

Contents

How Has the Rate of Inflation Changed

Over Time?

Should We Be Concerned About Inflation?

Is the Recent Surge in Inflation

“Transitory” or “Embedded”?

Money Supply, the Velocity of Money,

and Inflation

The Potential for a Wage-Price Spiral

On the Many (Other) Factors Affecting

Inflation

Inflation and Your Investment Portfolio

Inflation Basics

Inflation is typically measured, in the United States, by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, through a measure called “Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers” (“CPI-U”). CPI-U is a measure of the average change in prices paid by an urban consumer for a certain “basket” of goods and services. To determine this statistic, each month shoppers are sent out across the country to measure prices, and the data is then utilized to determine the rate of inflation.

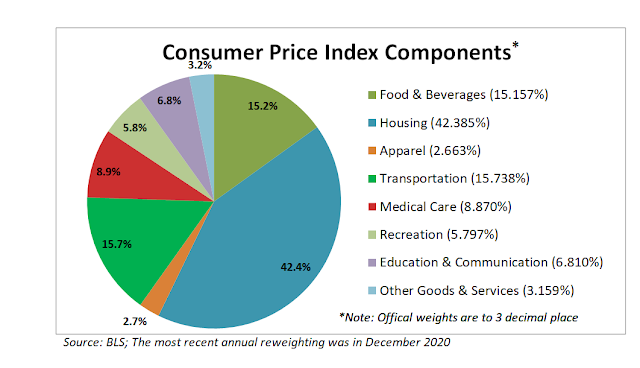

As seen in the chart below, housing (the prices of

single-family homes and condominiums, and rents) accounts for over 42% of the

measure of inflation. Medical care only accounts for 8.87% of CPI-U.

“Core CPI” is the measure of inflation that excludes

food and energy prices, which can be quite volatile. While policy makers often

pay attention to Core CPI, for consumers CPI-U is the better measure to watch.

Your personal rate of inflation – i.e., how

much you spend for the same basket of goods and services – can vary

significantly from the government’s measure. If your consumption patterns are

different, your personal rate of inflation will be different.

For example, suppose you own your own home. If you have a fixed

rate mortgage, or no mortgage at all, the cost of your home does not vary

significantly, and your personal rate of inflation may be lower. Refinancing a

mortgage to a lower rate can also cause you to lower the cost of home

ownership. However, certain housing costs, such as taxes, insurance, and

maintenance, can still increase over time.

Likewise, if you spend a lot on medical care, and the costs of medical care increase substantially, your personal rate of inflation can be higher. For example, health care spending increased substantially from 1980 to 2008, but since then health spending growth has slowed to a similar rate as the overall measure of inflation.[1]

How Has the Rate of Inflation Changed Over Time?

The rate of inflation (CPI-U) has been modest over the past

decade. But this was not always so. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, the rate of

inflation was much, much higher, as seen in this chart from EconoFact:

Here are the rates of inflation by decade:

Should We Be Concerned About Inflation?

Inflation is always a concern. Inflation is the

unstoppable economic force that slowly and steadily drains the purchasing power

from your dollars by driving the cost of everything up over time.

Modest inflation, such as that desired by the Federal

Reserve’s target of 2%, is It only somewhat facilitates the repayment of

long-term debt, provided that incomes increase over time. It also facilitates a rate

of return for savers in CD’s, bonds, and other fixed income investments. A

modest rate of inflation also stimulates spending by both businesses and

consumers, which in turn can drive economic growth. And modest inflation allows

wages to be adjusted upward.

But very high inflation, as seen in the late 1970’s and

early 1980’s, can be devastating – and difficult to stop – once it begins. High

rates of inflation create economic uncertainty, which can lower investment by

companies. Lending by banks becomes more precarious. The foregoing impacts

(lower investment, lower lending) can lessen economic growth. For consumers,

savings can fall in value (the “real return” – also known as the

“inflation-adjusted return” – on savings can be negative) when inflation is

high. If wages don’t keep up with inflation, “real wages” (wages, less the rate

of inflation) can go lower. And, if a high rate of inflation occurs in the

United States, but is less prevalent in other countries, over time inflation

can reduce our international competitiveness.

Is Inflation High

Today?

A high rate of

inflation is present, today, when comparing prices now to prices a year ago.

The U.S. Consumer

Price Index (CPI-U), the nation's key inflation measure, jumped 0.9% in June

2021 from the prior month; this was the largest one-month increase in 13 years.

Over the last 12 months, prices were up 5.4%, the biggest jump in annual inflation

in nearly 13 years.[2]

The recent surge in inflation is driven by many short-term factors, including:

·

Car Prices. The rise in new and used car

prices, due to shortage of computer chips for new vehicles, and the disruption

in 2020 of rental car fleets. Surging prices of used cars and trucks accounted

for more than one-third of the inflationary spike seen over the past year. The

retail price of used cars jumped 10.5% between May and June, following a 7%

jump the month before. However, The prices dealers pay for used cars at massive

auctions across the country dipped in June 2021 after hitting record highs for

much of early 2021, according to the Manheim Used Vehicle Value Index.[3]

o

The 10.5% increase in June in used car prices

was the largest one-month jump in records that go back nearly 70 years, and a

stunning 45.2% increase over the last 12 months. New car prices are also up

5.3% over the last year, hitting record levels.[4]

o

Car prices are being driven up by strong

consumer demand for cars, along with a limited supply due to a shortage of

computer chips needed to build the cars. Rental car companies, a key seller of

used cars, already sold off much of their fleet of cars last year to raise cash

during the pandemic and now don't have enough cars to rent. Yet, as the supply issues are resolved over

time, car price increases are likely temporary. Expect the prices of both used

and new cars to fall during 2022 and 2023.[5]

·

Home Prices and Rents. Due to low

interest rates, demand from millennials reaching peak homebuying age, and a

general shortage of single-family homes, housing prices have risen dramatically

recently. The National Association of Realtors estimated the rise of existing

home prices at 15.4% for the 1st quarter of 2021, from a year

before. New home prices increased 5.1% from the year prior.[6]

Prices, however, are projected by CoreLogic economists to only increase 3.4% over

the next year (from May 2021 to May 2022), as affordability challenges hit some

buyers and cause a slowdown in price growth.[7]

o Soaring home prices have had the effect of also raising rents, with a bit of a lag present. Data from Apartments.com shows average rent prices are up 7.5% year-over-year, which is three times the normal growth rate. CoreLogics’ April 2021 data shows a national rent increase of 5.3% year over year, up from a 2.4% year-over-year increase in April 2020. Rent prices vary widely, however, with rents actually on the decline (on average) over the past year in Chicago and Boston, while even higher rent increases than the national average were seen in many areas of Arizona, Nevada, Georgia, and Texas.[8] The future of home prices and rents is uncertain, as demand may be affected by many factors (including mortgage rates, demographic trends, etc.

· Oil prices. The following chart shows the 5-year trend of oil prices:

Source: Crude Oil Price Today, retrieved

7/13/2021.

As seen, the substantial dip in oil prices due to

decreased travel and decreased economic activity at the inception of the

COVID-19 pandemic has, over the past year, been negated by jumps in oil prices.

This has occurred largely via production cuts by OPEC countries (and Russia),

and by the increases in travel and other economic activity in recent months.

Yet, OPEC’s ability to stick to oil production cuts are in large part unpredictable, due in large part to continued arguments among OPEC countries about market share.[9]

It should be noted that since July

10, 2020 the number of oil rigs in production, in the United States and Canada,

increased from 287 to 616.[10]

Furthermore, the number of crews finishing off previously drilled wells in the

United States has increased this year from 70 to 234, indicating more oil

production is posed to come online.[11]

The U.S. Energy Information

Administration stated on July 6, 2021: "We expect rising production will

reduce the persistent global oil inventory draws that have occurred for much of

the past year and keep prices similar to current levels, averaging $72 per barrel

during the second half of 2021.” For 2022, EIA said it expects growth in

production from OPEC+ and U.S. tight oil production, along with other supply

additions, will outpace growth in global oil consumption and contribute to

declining oil prices.[12]

Is the Recent Surge in Inflation “Transitory” or “Embedded”?

To summarize the prior section, car prices – which have

contributed one-third of the rise in the Consumer Price Index (year-over-year)

as of June 2021 (per BLS), will likely decline over the next couple of years.

The “supply shock” cause of increased car prices (driven in part by a shortage

of consumer chips) is temporary in nature.

Oil prices are largely unpredictable, due to OPEC politics,

but increased production in the U.S. and Canada may lead to greater increases

in oil production than increases in demand over the next year or so. (Source:

U.S. Energy Information Administration, This Week in Petroleum, July 8, 2021.)

OPEC may, however, further cut production. Or, at time OPEC countries may

diverge due to disagreements on market share, and OPEC countries might increase

production when OPEC nations fail to reach consensus.

Housing prices may be in a “bubble” in some markets, at

present, as the cost of housing exceeds the reasonable cost of construction in

many suburban areas. While housing prices may well continue to rise for another

year or more, at some point new home construction will likely catch up with

demand, resulting in a lowering of home prices. Housing rental rates will

likely increase over the next year, as they are affected by housing prices, but

may stabilize thereafter.

If we were to stop there, we might assume that the rate

of inflation seen in 2021 – now at 5.4% year-over-year – might fall in future

months, and certainly the rate of inflation would appear destined to fall in

2022. In part this is because depressed pandemic levels from a year ago

translate to artificially higher year-over-year rates, but that explanation is

less sufficient for June. While the base effect hasn’t entirely faded, it is

diminishing. Also, stripping out volatile items like food and energy, “core”

CPI rose only 4.5% year-over-year in June 2021.[13]

However, economists, as well as those undertaking policy

decisions at the Federal Reserve are engaged in a fierce debate about the risk

of runaway consumer prices fueled by ultra-accommodative fiscal and monetary

policy. In other words, vast government spending, combined with low

short-term interest rates (influenced by the Federal Reserve) and purchases of

fixed income securities by the Federal Reserve (which has the effect of

introducing more cash into the banking system – resulting in money supply

growth).

Hence, an even deeper dive is warranted, to even attempt to

answer the question – is higher inflation in our future.

Money Supply, the Velocity of Money, and Inflation

According to traditional economic theory, money supply

growth and inflation are inexorably linked. As seen in the following chart from

the Federal Bank of St. Louis, money supply (as represented by M2 Money

Stock) has substantially increased since the pandemic began:

Yet, the “velocity” of money – the rate at which money changes hands (typically measured over a one-year period) has declined substantially over the past twenty years, as seen in this chart from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (showing money velocity from 1959 through 2020):

The velocity of money in the United States is calculated by dividing the nation’s economic output, nominal GDP — GDP not adjusted for inflation — by the money supply. When the velocity of money is high, a dollar is changing hands frequently to purchase goods and services — suggesting that the economy is doing well. It reflects high demand, which generates more economic activity. When the velocity of money is low, a dollar is not changing hands often to buy things — meaning that economic activity is sluggish. Instead, it is being saved and invested.

To get sustained inflation, we will likely need a pickup in

the velocity of money. In other words, we need banks to hold less in their

reserves, and to loan out that money to businesses and consumers (which is

largely not occurring today, relative to the amount of cash available. And we

need consumers to spend their savings (which is occurring, to a degree).

So, to summarize – a huge increase in the supply of money is

inflationary, but not so much if the velocity of money has declined (as it did,

substantially, from March 2020 to today). Whether the velocity of money

will substantially increase is unknown, as it is affected by many factors,

although I believe a slight pick-up in money velocity in the second half of

2021 is likely. This, in turn, would tend to favor higher inflation.

But inflation is driven by many other factors, other than

just money supply and the velocity of money (which many economists and

investors have focused upon).

The Potential for a Wage-Price Spiral

In my personal opinion, while the large money supply and

the potential for higher interest rates (and increases in the velocity of

money) are a substantial concern, the largest inflation threat comes from the

potential of a wage-price spiral – which would in turn trigger higher interest

rates.

Wages across the United States are increasing – often

dramatically.

When wages rise steadily and consistently over time, those

higher earnings don’t trigger sharp inflation. But sudden and dramatic

economy-wide wage increases certainly can. That kind of fast nationwide pay

raise usually comes from one of two economic drivers — a hike in the minimum

wage or a dramatic reduction in the supply of labor.

As reported in NFIB’s monthly jobs report, 46% of owners

reported job openings that could not be filled, a decrease of two points from

May but still historically high and above the 48-historical average of 22%.[14]

Many companies big and small are increasing compensation,

but even that has not been enough to do the trick. This year a record number of

firms raised wages and benefits in an effort to lure new hires and to retain

valued employees. Large businesses voluntarily increasing their wages include

Target ($15 per hour), Hobby Lobby ($17 per hour), Starbucks (10% increase in

all wages), Costco ($16 per hour), Walmart ($13 to $19 per hour for workers,

with half of company’s employees making $15/hour or more), McDonald’s 650

corporate locations ($11 to $17/hour for entry-level crew), and Amazon $15 per

hour). A recent study found that Amazon’s pay raise resulted in a 4.7% increase

in the average hourly wage among other employers in the same labor market

(commuting zone).[15]

A net 39% (seasonally adjusted) of small businesses reported raising compensation, a record high. A net 26% of small businesses plan to raise compensation in the next three months.[16]\

Wage increases are not just voluntarily undertaken by companies. Many states and localities have enacted minimum wages which are far above the federal minimum wage of $7.25, as seen in this recent map produced by Workest:

To help offset the higher cost of supplies and labor, a net 47%

of small business said they raised prices in June — the highest reading in 40

years. [17]

The question remains, however, as to whether the higher

wages recently seen, which have led (and will lead) to increases in the prices

of goods and services, will then trigger further wage increases. In other

words, as the prices of goods increases, will workers demand even higher wages

– which will then trigger higher price increases – which then trigger higher

prices – etc.

And that is the great unknown. Still, I personally estimate a 25% chance of wage-price inflation becoming “embedded” in the economy, and persisting until fiscal and monetary policy changes (higher interest rates, lowering the supply of money, reduced federal spending, etc.) bring such a wage-price cycle under control.

On the Many (Other) Factors Affecting Inflation

The uncertainty about inflation occurs because inflation is

driven by many different factors, not just those discussed above.

Several longer-term trends and near-term developments are

supportive of higher rates of inflation:

· A decrease in “globalization” may occur. The import of low-cost goods has tampered inflation over the past 30 years. Core prices for goods rose just 18% between 1990 and 2019, while prices for core services (produced domestically) rose 147% over that time period.[18] However, will trade wars erupt (including less imports from China)?

· The labor force is not expanding as rapidly, and in some areas is shrinking, due to the decline in the number of working-age adults in many countries. According to a United Nations report, U.S. working-age population growth will slow to just 0.2% a year between 20202 and 2030, down from 0.6% in the decade earlier. (Increased immigration, if permitted, could offset some of the labor shortages projected, especially among skilled workers.)

· Another trend favoring a higher rate of inflation is the large fiscal stimulus that may occur via direct-to-consumer payments (expansion of the child tax credit, for example) and increases in government spending (whether on infrastructure, renewable energy incentives, or otherwise). On July 13, 2021, leading U.S. Senate Democrats agreed on a $3.5 trillion spending plan, that will form the basis of the reconciliation package (that can be enacted without Republican support, later this year, if all Democrats support the final package).

Yet, there are forces present which would tend to lower inflation, and even lead to deflation, such as:

· An increase in productivity can be an inflation-killer. Due to investments made by companies during the pandemic in information technology and robotics, productivity on a year-over-year basis is at its highest point in a decade. From the second quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021, labor productivity in the nonfinancial corporate sector jumped 5.3% while hourly compensation rose 2.0%.[19]

· The concentration of wealth, now at its highest since World War II,[20] can result in less consumer spending. Those who have amassed more wealth possess a far lower marginal propensity to consume, when they receive additional income, than those who are far less wealthy. However, with strong indications that the U.S. equity markets (overall), bond markets, and real estate markets are all overpriced, a downward correction in prices would mitigate some of the wealth inequality seen.

· Commodity prices have already surged, and projections of commodity prices going forward (particularly food, energy) indicate the potential for lower prices. Commodity price increases appear to have driven in part by supply-side constraints, which tend to correct over time. (However, there is always a great deal of uncertainty about commodity prices, especially in the near term.) Also, by 2025-2030 peak demand for oil might occur, due in large part to the continued deployment of solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources, and the rapid decline in the sale of gas-fueled vehicles expected from 2025 through 2035.[21]

· The chief problem facing most of the world's developed economies today is the level of outstanding debt, both private and public. Whilst the creation of debt can represent an expansion in the broad money supply, the destruction of debt conversely equates to a contraction in the money supply. As all debts must eventually be repaid, debt by nature is deflationary over time.

In conclusion, while much of the rise in recent wages and

prices appears to be one-time adjustments, there is the possibility of

sustained inflation over the next few years. While the Federal Reserve has

stated that it has the tools to constrain inflation should it continue, there

is a fear that the Federal Reserve is over-confident in its own abilities,

given the historical difficulties seen in bringing past wage-price spirals

under control.

Inflation and Your Investment Portfolio

If inflation does continue for a few years (or longer),

what does it mean for your investment portfolio?

Traditionally, commodities have been an inflation edge. But,

increases in commodity prices have already occurred, as noted above.

Another hedge against inflation has been real estate. Yet,

home prices appear to be in a “bubble,” and office vacancies continue in large

numbers. Vacancy rates for industrial properties, such as warehouses, are

already quite low, with rents for industrial buildings already rising 7.1% in

the first quarter of this year from a year prior.[22]

Should interest rates increase, the valuations of growth

stocks will be put under pressure. Value stocks, while not an inflation hedge,

will likely perform well relative to growth stocks, although value stocks are

not necessarily an inflation hedge.

The following investment strategies, in particular, from

ARGI may perform well in a higher inflation environment, should it occur (and

should also perform well, relative to the market, due to overvaluations in U.S.

large cap growth stocks, as will be discussed in a future edition of Da Bear’s

Perspectives):

Dividend

Select Portfolio

Defensive Equity Portfolio

Factor 15 Small Cap Portfolio

Note that higher interest rates, often used to combat

inflation, can result in lower returns for growth stocks (as a broad asset

class), in part because future earnings of growth stocks are subjected to a

higher discount rate under traditional stock valuation methodologies. All of

the above ARGI investment strategies employ investment “factors” that tend to

tilt away from growth stocks, to some degree.

Over the very, very long term, stock prices often adjust

with inflation. This is because, as prices increase, so do corporate revenues,

which in turn ultimately drive higher earnings. However, as evidenced by

the performance of the U.S. stock market in the 1970’s, the overall valuation

of stocks can be driven substantially lower should inflation, and interest

rates, rise dramatically. In combatting inflation via higher interest rates,

bond investments are made more attractive to investors, and equities (stocks)

less attractive, leading to potential undervaluation in stocks (relative to

norms).

Long-term bonds would likely fare poorly should inflation

surge, as interest rates would also likely rise. (Bond prices fall when bond

yields rise.) Short-duration bond portfolios are likely to perform better. A

bond ladder, observant to making proper investments given the present yield

curve, is also a good strategy for the long-term, regardless of inflation.

Inflation-adjusted bonds would appear at first to be a wise

choice. Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) and I-bonds are issued

and backed by the U.S. government. However, TIPS operate a bit differently than

traditional U.S. Treasury bonds. Investors receive regular interest payments

based on the face value of the bond until it matures. Investors also receive

inflation protection, via a yearly adjusted par value that derives from CPI-U,

the U.S. government’s primary measure of inflation. This changing yearly value

is intended to maintain the TIPS’ purchasing power over time. However, recent

demand for TIPS, which are now issued in 5-, 10-, and 30-year terms, has been

quite strong; as a result, TIPS’ yields are currently negative, with investors

betting that TIPS’ future inflation payments will make holding them worthwhile.

Still, a shorter-duration TIPS bond ETF may form part of a portfolio, and

provide some protection against possible future higher inflation.

Timing the market is difficult, as is predicting future

inflation. Hence, any adjustments in your investment portfolio should

ordinarily be undertaken using a longer-term view, and considering the

consequences if inflation increases or remains low.

Until the next time …

Very

truly yours,

Ron (Da

Bear)

Email: bear@argi.net

Dr. Ron A. Rhoades serves as Director of the Personal Financial Planning Program at Western Kentucky University, where he is a professor of finance within its Gordon Ford College of Business.

Called “Dr. Bear” by his students, Dr. Rhoades is also a financial advisor at ARGI Investment Services, LLC, a registered investment advisory firm headquartered in Louisville, KY, and serving clients throughout most of the United States.

The author of the forthcoming book, How to Select a Great Financial Advisor, and numerous other books and articles, he can be reached via: bear@argi.net.

[1]

KFF analysis of National Health Care Expenditure (NHE)_ date Personal

Consumption Price Index (PCE) from Bureau of Economic Analysis

[2] U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

[3]

Scott Horsley, “Inflation Is Still High. Used Car Prices Could Help Explain

What Happens Next.” NPR (July 13, 2021).

[4] U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

[5] Tim

Levin, “Why used cars are so expensive now — and when prices may drop,”

Business Insider, July 12, 2021.)

[6]

National Association of Realtors, U.S. Economic Outlook: May 2021

[7] CoreLogic

U.S. Home Price Insights, July 6, 2021

[8] CoreLogic,

June 15, 2021 release

[9] BOE

Report, “OPEC+ impasse risks price war as demand surges, says IEA”

[10] Baker

Hughes Rig Count Overview

[11]

Julianne Geiger, U.S. Rig Count Rises in Volatile Week for Oil, oilprice.com

(July 9, 2021), citing the Frac Spread Count provided by Primary Vision.

[12]

Devika Krishna Kumar, “U.S. 2021 crude output to decline less than previously

forecast, EIA says,” Reuters, July 7, 2021

[13] U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

[14] National

Federation of Independent Business, which represents small businesses in the

U.S., monthly jobs report

[15] Derenoncourt,

Ellora and Noelke, Clemens and Weil, David, Spillover Effects from Voluntary

Employer Minimum Wages (February 28, 2021)

[16] National

Federation of Independent Business, monthly jobs report

[17]

National Federation of Independent Business, which represents small businesses

in the U.S., July 13, 2021 release

[18] The

Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2021

[19]

Gary Shilling, “How Labor Shortages Help Profits and Hurt Inflation,” Bloomberg

(July 1, 2021)

[20] Ray

Dalio, Bridgewater Associates

[21] Noah

Browning, “Factbox: Pandemic brings forward predictions for peak oil demand,”

Reuter (April 21, 2021)

[22] CBRE U.S. Industrial and Logistics Figures Q1 2021